BAT PUPS LEARNING TO FLY

News Release

July 24, 2023 OKANAGAN AND SIMILKAMEEN REGION, BC – Are you noticing more bats around your house or property? You are not alone! Mid-summer is the time when landowners typically notice more bat activity, may have bats flying into their house, and occasionally find a bat on the ground or roosting in unusual locations.

These surprise visitors are often the young pups. “In July and August, pups are learning to fly, and their early efforts may land them in locations where they are more likely to come in contact with humans“, says Paula Rodriguez de la Vega, Okanagan coordinator with the Got Bats? BC Community Bat Program.

As noticed in the last two years, heat and smoke may also cause bats to use unusual roost sites.

If you find a bat, alive or dead, remember to never touch it with your bare hands. Bats in BC are known to carry rabies at a low level; this is why it is important to avoid any contact. If you must move a bat, use a trowel or similar tool, and always wear leather gloves to protect yourself from direct contact. Talk to your children to make sure they understand to never touch, play or try to rescue injured or sick-looking bats. If you suspect a bite or scratch from a bat, immediately wash the area with soap and water for 15 minutes. Also contact your public health or your doctor as soon as possible, or go to the emergency department.

For more information on rabies please refer to the BCCDC website http://www.bccdc.ca/health-info/diseases-conditions/rabies.

“Bats are important to our ecology and economy. They are the main consumers of night flying insects. Unfortunately, bats are in trouble, and half of the bat species in BC are listed as ‘at risk’,” says Rodriguez de la Vega. Bats are often found in close association with humans, as some species (such as the Little Brown Myotis) have adapted to live in human structures, and colonies may be found under roofs or siding, or in attics, barns, or other buildings. Female bats gather in maternity colonies to have a single pup in early summer, where they will remain until the pups are ready to fly.

“Having bats is viewed as a benefit by many landowners, who appreciate the insect control. Others may prefer to exclude the bats,” says Rodriguez de la Vega. Under the BC Wildlife Act it is illegal to exterminate or directly harm bats, and exclusion should only be done in the fall and winter after it is determined that the bats are no longer in the building. If you have bats on your property, the BC Community Bat Project can offer advice and support.

You can keep bats out of your living space by keeping doors and windows closed and ensuring window screens do not have any holes. If you find a live bat in a room of your home, open the window and close interior doors until the bat leaves, or follow the steps here: https://batworld.org/what-to-do-if-youve-found-a-bat/. “Cat predation is a very common cause of death of bats in BC, which is bad for bat populations and potentially exposes the cats, and their owners, to rabies,” says Rodriguez de la Vega. Keep cats indoors, particularly overnight when the bats are most active, and ensure all cats are vaccinated for rabies.

This student is pointing at a bat roosting at the top of the doorway at the entrance of her school. Bats should be left alone unless they are roosting low down where children or pets can come into contact with them. These are great opportunities to teach about bat conservation and safety. Never touch a bat. Leave it alone and it will fly off at dusk or after a few days. Photo by P. Rodriguez de la Vega.

For information on safely moving a bat if necessary and to report bat sightings, landowners can visit the Got Bats? BC Community Bat Program’s website (www.bcbats.ca), email [email protected], or call 1-855-9BC-BATS ext.13. The BC Community Bat Program is supported by the BC Conservation Foundation, the Habitat Conservation Trust Foundation, the Forest Enhancement Society of BC, the Habitat Stewardship Program, the Government of BC. In the Okanagan, we partner with the Allan Brooks Nature Centre in Vernon, the RDCO Environmental Education Centre for the Okanagan in Kelowna, the Bat Education and Ecological Protection Society in Peachland, the Thompson Okanagan Tourism Association, the Osoyoos Desert Centre and many others.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

Paula Rodriguez de la Vega

Okanagan Region Coordinator, BC Community Bat Program

Toll free: 1-855-922-BATS (2287) ext.13

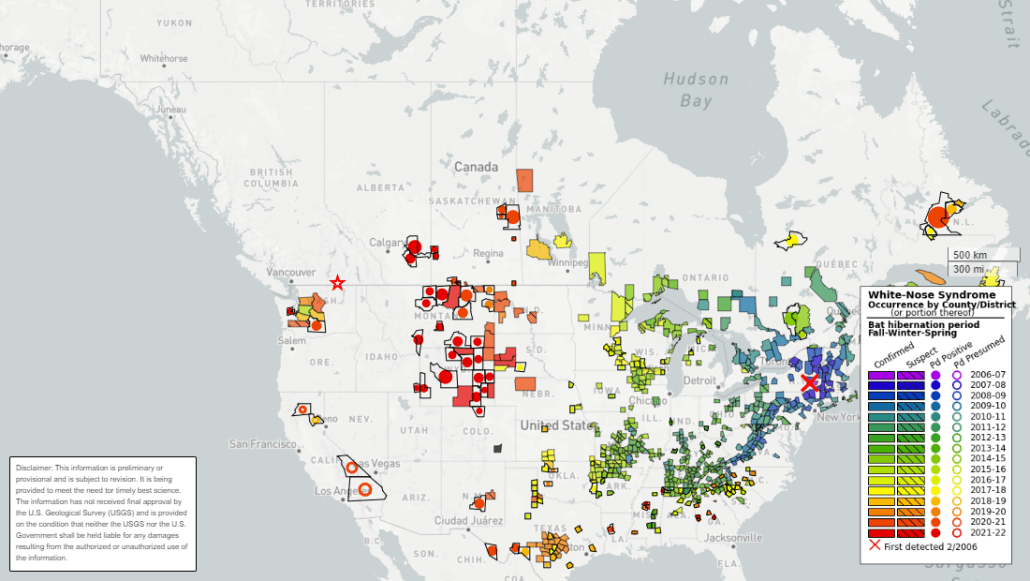

Help us detect white-nose syndrome in B.C. Please report dead bats and unusual bat activity in winter. Call our toll free line: 1.855.922.2287, ext.13. For more information see www.bcbats.ca.