Insects are by far the most populous wildlife species on Earth, and their numbers have been drastically declining in the past few years.

Eminent biologist and author E. O. Wilson says, “If insects were to vanish, the environment would collapse into chaos.”

So why aren’t more people concerned? Are you?

Insects are the very backbone of ecology.

They’re nature’s vital pollinators, decomposers and recyclers of waste, soil builders, other insect and weed regulators and the base of food webs everywhere.

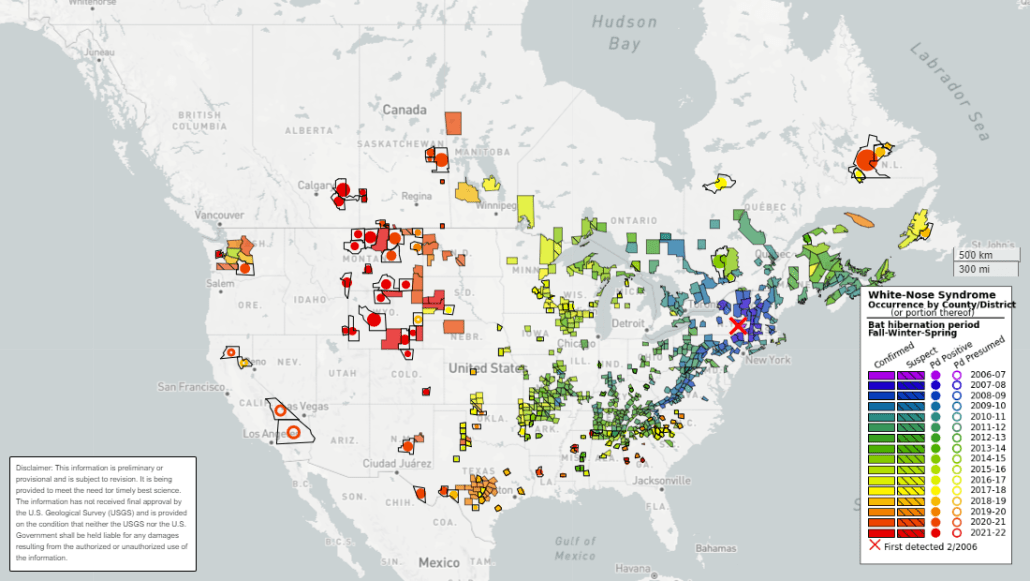

They pollinate almost 90 per cent of flowering plants and 3/4 of our crop species – a service worth around $500 billion annually. And they’re food for most of our songbirds, freshwater fish, reptiles, amphibians and all of our bats.

Aerial insectivores like swallows, swifts, flycatchers, bats and many others have been starving and declining over the past 50 years because of habitat destruction and insect declines.

By eating and being eaten, insects turn plants into protein, and power the growth of insectivores, then move up the food chain to power all the animals that eat them. Think about bears who depend on insects to pollinate their berries. And the insects that sustain young salmon.

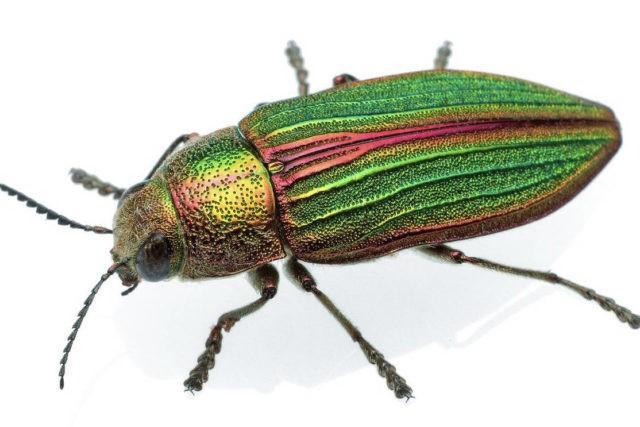

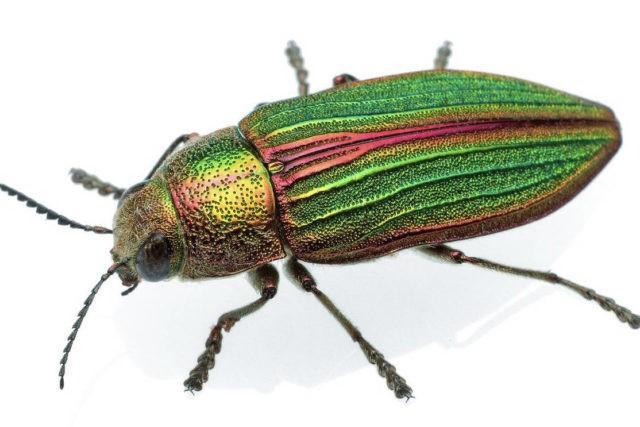

And what about us? Insects are vital to the decomposition that keeps nutrients cycling, soil healthy, plants growing and ecosystems running – an invisible role until it stops. Insects are worthy of our admiration and respect.

Anyone born before 1970 will remember the problem of insect bodies plastering car windshields and grills which is rarely a problem now. So gas station attendants regularly washed windshields while gassing up. And you’d see insects in headlight beams when driving at night. Also, moths would flit around lampposts on summer nights, or be resting on your entry wall if you kept your light on overnight.

Scientists have named and described a million species of insects including 12,000 species of ants, 20,000 species of bees, 400,000 species of beetles…on and on. And there are millions of unknown species of insects and other terrestrial invertebrates (arthropods such as insects, spiders, ticks, scorpions, centipedes, etc.).

We call insects whose lives intersect most intimately with our own – mosquitoes that bite us, ants at our picnics, flies on our windows, etc. – “Bugs.” (True bugs are the 80,000 Hemiptera insect species with tube-like mouths for sucking, not chewing, such as aphids, stink bugs and cicadas.)

Sometimes we feel that we know insects too well. But really they are one of the planet’s greatest mysteries – a reminder of how little we know about the world around us.

Only about two per cent of insect species have been studied enough for us to estimate whether they are in danger of extinction, never mind what dangers that extinction might pose. The few scientists studying insects’ drastic decline call it an insect apocalypse or Armageddon.

Our natural world thrives on the richness of complexity and interaction called biodiversity. The more interactions lost, the more ecosystems break down.

Conservation tends to focus on rare and endangered species, whereas it is the common ones like insects, because of their abundance, that power the living systems of our planet.

“It’s the little things that run the natural world,” says E.O. Wilson.

Stay tuned: July’s Get Outdoors column will describe the insect decline causes and what we can do to help.

Roseanne Van Eeenthusiastically shares her knowledge of the outdoors to help readers experience and enjoy nature. Follow her on Facebook.

Every day hundreds of people walk, jog or cycle sections of the Grey Canal’s scenic trails that surround Vernon and the Coldstream Valley.

Every day hundreds of people walk, jog or cycle sections of the Grey Canal’s scenic trails that surround Vernon and the Coldstream Valley.

Our birds need winter berries; they’re the perfect size fruit. Resident birds that don’t migrate, but remain here year-round, need food and warmth to survive the harsh winters. Most songbirds (aka passerines or perching birds) are seed and berry eaters.

Our birds need winter berries; they’re the perfect size fruit. Resident birds that don’t migrate, but remain here year-round, need food and warmth to survive the harsh winters. Most songbirds (aka passerines or perching birds) are seed and berry eaters.